Why We Can't Govern Cities: Rousseau, Locke, and the Good Woman of Seztuan

Are people inherently good? Or are they inherently disappointing?

A few days ago on the Pod Save America podcast, Ezra Klein made news when he discussed a topic that’s long been taboo for Democrats: the governance of America’s major cities. Nearly every major city in America is under full Democratic control. As everyone knows, their governance has not been good.

It’s not just that there’s crime. America’s cities feel a bit lawless, with shampoo bottles locked up in drug store cabinets due to unpoliced shoplifting. Cities aren’t just expensive. In many cities, it’s all but impossible for a teacher or firefighter to afford a home inside the same city they serve. Transit is shoddy. Public services are poorly provided. It’s nearly impossible to build new things after all the reviews and meetings and checklists. Many ordinary Americans are outright afraid to visit, much less live in, a major city.

There’s no plausible excuse. Nationally, Democrats complain their policies would create a better nation if it weren’t for Republican obstruction. There’s no Republicans to obstruct Democratic policies in cities. Democrats say there’s a lot of poverty in cities. There’s also an insane amount of wealth. Two of America’s worst governed cities are San Francisco—the home of the technology industry—and New York City—the world’s financial hub. If there’s not enough money in those places to implement your policies, there’s not enough anywhere on earth.

It's an uncomfortable juxtaposition of intentions against results. Democrats claim to be the party of smart policy and good government. They claim to care about people. They say they want ordinary people to have good lives in nice places to live. Yet when Democrats get free reign to govern on the largest stages with massive budgets and zero opposition, the results are nothing like the promises.

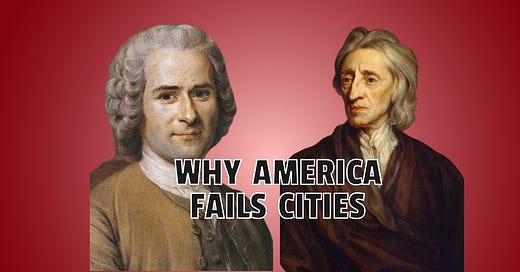

It’s not a problem of intentions. It’s a problem of philosophy—Locke vs. Rousseau. Democrats are too much Rousseau. They believe people are inherently good. They need to be more Locke.

THE GOOD WOMAN OF SEZTUAN

One of my favorite plays is The Good Woman of Seztuan by mid-century German playwright Bertolt Brecht. In the play, the gods come down to earth looking for just one good person. If they can’t find one, they’ve resolved to destroy the world and start again. The gods wander in the guise of poor travelers, and everyone treats them horribly. Finally, desperate for a place to sleep, the gods find no one willing to offer them a bed, until they run into an impoverished prostitute. A kind person, the prostitute refuses to turn people in need away, so she offers them the little that she has. Relieved they found one good person, the gods give the woman a large sum of silver as a reward so she can change her life.

To launch her new life, the prostitute buys a little tobacco shop. As word spreads of her new circumstances, however, it’s soon overrun by locals hoping to take advantage of her good fortune. They lounge about taking her stock without paying. They demand money, offering implausible sob stories. As a good person, the women eagerly helps them all as her funds slowly drain away. Soon she’s at risk of returning to the streets.

Then her brother, a stern and savvy businessman, arrives in town.

Dismayed at the state of things, the brother takes over the shop and his sister all but disappears. Unlike his sister, the brother is tough and ruthless. He runs off the freeloaders. He takes charge of the little store and starts expanding. Soon it becomes a profitable tobacco factory. The factory expands, and the brother puts the freeloaders to work. They’re happy for the opportunity and they treat him with respect, and even reverence. The entire village begins to thrive.

The sudden disappearance of the woman, however, interests the police. They suspect the brother did something awful to steal his sister’s fortune. When they arrest him, the gods return disguised as judges in the case. It’s revealed the brother does not in fact exist. It was the woman in disguise.

Fearing her good nature would throw her back into poverty, the woman assumed the alter ego of her brother to save herself. The world didn’t reward goodness, so she became the person she needed to be to survive in the world as it was. When she reveals herself to the gods, the woman laments it was impossible for her to live in this world and remain good. Refusing to even consider the contradiction, the gods dismiss her pleas and tell her she’s still a good person. Then they fly away leaving the question unresolved.

What I find most interesting about the play is Bertolt Brecht was no Ayn Rand libertarian. He was a German Marxist who fled Nazi Germany for California, where he was later investigated by the House Un-American Affairs Committee for his communist sympathies.

ROUSSEAU AND LOCKE

When I talk to friends on the political left, I like to ask if they believe people are inherently good. I’m shocked at how often they tell me people are. This rarely happens with friends in the center or on the right. In fact, if I had to guess at what philosophically makes someone choose the political left today, I suspect it’s this belief that people are generally good and society makes them bad. They side with Rousseau.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau is the philosopher most associated with the belief that people are inherently good and society is the cause of the world’s wretched state. Rousseau believed people naturally were good and in the state of nature they were, as he put it, “noble savages.” Society, Rousseau believed, had corrupted people and pushed them towards evil acts.

If you think Rousseau is right about people’s nature, it leads to certain beliefs about how to build a good society. If society makes people evil, creating a better society means choosing better structures that allow people to revert to their natural goodness. You remove society’s structures and constraints encouraging and rewarding selfishness and cruelty. You remove the corrupted few at the top, so the majority of good people can take back their power. Through enlightenment and education, you reengineer people to behave as their natural nature wills. You create a kinder, more fair, and more prosperous society by combating the bad forces of civilization causing people to turn toward evil, allowing them to revert to good.

Rousseau is credited as the French Revolution’s philosopher, since that revolution was an attempt to bring these principles to practice.

The alternative view of humanity is Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and the philosophers of the British side of the Enlightenment. They all believed that, while people aren’t exactly evil, they’re altogether disappointing. They didn’t believe the state of nature was the noble savage but, as Hobbes put it, a life that was solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. They recognized people are capable of wonderous things—kindness, intelligence, creativity, and productivity. They’re also, however, capable of terrible ones—stupidity, selfishness, sloth, and cruelty. We can shorthand this conception of humanity’s nature as Locke.

If you believe Locke over Rousseau, you find humanity not good but a mixed bag. Some people genuinely are angels. They’re loving, giving, creative, and kind. Most are good or bad depending on the situation. In some situations and with some people, most humans can be kind, loving, and fair. In other situations and with other people, however, the very same humans can be selfish, wicked, and cruel. Finally, there’s the few who are simply evil. They’re cruel, heartless, selfish, hateful, and dangerous by nature. They aren’t just indifferent to suffering but enjoy inflicting it.

Under Locke’s conception of humanity, nobody made bad people into bad people. Nobody hurt them. There were no circumstances that twisted them. They weren’t victims of bad parenting. There’s nothing any school could teach them to change their nature. They were the little boys and girls from loving families who enjoyed torturing dogs and cats because they were curious and enjoyed the feeling of power hurting something living gave them. They were born the way they are.

If you believe people are frequently disappointing, however, you believe creating a just and fair society requires different solutions than Rousseau. You don’t see society as an evil force making people do bad things. You see it as a civilizing force constantly at odds with human nature to push people to be better. You don’t see policy as a means to strip away oppressive structures so human goodness can flourish. You see it as building wise structures that limit people from exploiting or hurting others, hoping to construct spaces in which oppression is limited if not removed.

Locke’s view leads to something like a representative democracy with checks and balances against power—which makes sense since America’s Founders were adherents of Locke and his side of Enlightenment thought. While the French Revolution is Rousseau in action, America’s Founding is Locke.

MORE LOCKE AND LESS ROUSSEAU

The reason Democrats have been unable to govern, in America’s cities specifically, has roots in their deep belief in Rousseau over Locke.

Democratic policies make sense if you presume people are inherently good and it’s the society around them that makes them act badly. If that’s the case, you want to show compassion to those taking advantage of others or disrupting public order because it isn’t really their fault. It’s the fault of the bad people who created the structures they’re reacting too. What you want to do instead is show compassion while working to remove the bad people and structures causing them to misbehave.

This is exactly what Democratic, and left-leaning, policies try to do. They target structural inequities. They extend compassion to lawbreakers and violators of public order. They treat people like blank slates, seeking to educate them to unleash their true nature. They hunt for the wicked few that corrupted the system, creating public enemies and scapegoats. They don’t seek to penalize or punish, because that’s targeting the wrong problem. They don’t try to build structures or rules to control or limit bad behavior, because rules and procedures are the cause of oppression not it’s liberator. You act like the Good Woman of Seztuan. You try to be good and expect it will free others to be good as well.

If you believe Rousseau was wrong, however, this all seems like insanity. If you believe most people are disappointing and society civilizes and frees people instead of oppresses them, you don’t just remove all civilizing forces and let people to do as they want. Many will exploit and hurt others, making the angels among us into their victims. If the great mass can be good in the right circumstances, but selfish or cruel or stupid in the wrong ones, you’re encouraging people to become their worst selves instead of their best. As for the truly wicked, you’re just letting them run wild destroying and hurting others without limit. They can’t be educated into becoming better people, only confronted and controlled to protect everybody else.

I wonder about how many of our current political disagreements are truly disagreements about where we need to go. I find most Americans, right or left or otherwise, agree on the basics of a good society. They want everyone to have good lives. They want everyone to be treated with respect. They want widely shared prosperity. They want people to be safe. They want things to work. The true disagreement is simply how to get there. This in turn is mostly a disagreement about human nature. It’s a disagreement between Locke and Rousseau.

I also suspect Rousseau is popular among the upper-middle class and professionals because they’re the people in society most insulated from the worst the world can offer. They mostly come from good families, raised by good people. They go through life inside institutions with others similarly raised. They rise through these institutions because they’re conscientious and rule-following. They wind up in professions among others just like them. Those among their group who aren’t good are smart and Machiavellian, able to blend in and hide their nature like chameleon predators rising to the top. Why wouldn’t people from this world believe people are inherently good, and it’s the world that makes them bad?

I still favor Locke. I don’t believe people are inherently evil, but I also don’t believe they’re mostly good. I think they’re a mixed bag, and some are better than others. Most people are capable of amazing love, honestly, openness, creativity, and selflessness in the right circumstances. They’re also capable of staggering cruelty and harm in the wrong ones, like in Hannah Arendt’s banality of evil. Some people, moreover, are simply demons in human skin, preying on others for the love of the power and pleasure it provides them. They can’t be reasoned with or educated, only confronted.

Basically, I think America’s Founders got it right. The goal of policy shouldn’t be to free people from bad systems making them act bad, but to create good systems that encourage people to be good while limiting the harm of exploiters who refuse to cooperate. Power isn’t just a tool to create a better world, but also the means by which people do harm, and the only defense against it is to pit power and interest against power and interest. Since some people are exploiters looking for victims, society must ruthlessly protect others from their exploitation. The power of the state must protect people from abusers and exploiters, while the people must protect each other against abuses from the state. Over all, society should actively help people obtain the resources and tools they need to become their best selves, while also limiting the ability of people to exploit others and indulge their worst impulses and desires.

I’m not sure what can be done about this. I do know until the left comes to terms with the blind naivety of Rousseau, it can never govern well. It will certainly fail in the most competitive and high-stakes jungles of humanity, major cities. All the wonkish study, policy ideas, and political will can never work if it’s all based on a false understanding of people. The nature of people is closer to Locke than to Rousseau.

Do you agree with Locke or Rousseau? Join the conversation in the comments.

I read the Federalist papers in college and taken their dim view of human nature as my own, and never been disappointed by political behavior ever since.

Marxists were not bleeding heart liberals. Stalin eradicated homelessness in Soviet Union using working penal colonies among other things.