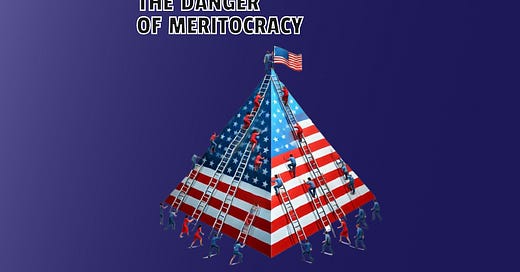

Reflections on the Dangers of Meritocracy

The idea of meritocracy isn’t the problem. “The Meritocracy” is the problem.

We have a meritocracy problem in America. The idea of meritocracy isn’t the problem. “The Meritocracy” is the problem. In a sincere effort to bring about a better nation built upon competence and effort in which anyone through hard work and talent could rise, we unwittingly created a broken, detached, tone-dead administrative class unwittingly subverting the very values it’s meant to honor and advance.

We need to talk seriously about meritocracy, both the idea and “The Meritocracy” that now exists. How and where did we go wrong?

THE PROBLEM OF LEADERSHIP IN A DEMOCRACY

Among the greatest debates of America’s Founders was how to create a ruling class without an aristocracy. In old world Europe—and with a few exceptions for most of the world throughout history—national leaders were forged through aristocracy. The new American republic would allow the people to vote for representatives to govern, but it would still need trained and competent officials, administrators, and military officers carrying out their orders. Where would we find such people without aristocrats?

Aristocrats weren’t just dilettantes squandering the nation’s wealth on frivolities, but a hereditary ruling class expected to lead. The nation expected them to fill the ranks of government ministers, military officers, and bishops. Aristocrats were therefore trained from birth to become future leaders for their nation. They were expected to read important works, learn to lead men in battle, and hone their manners with codes of propriety and honor. Their wealth and power came with obligation.

Aristocracy, in other words, was a solution to the difficult problem of training leaders and competent administrators of state. This was the great question going back to Plato’s Republic, in which Plato set out his ideas for the ideal city. Plato devoted most of his work to an elaborate scheme to craft and educate a public-spirited ruling class that was competent, wise, noble, and not-corrupt—his “philosopher kings.” Not every aristocrat would fulfill these expectations, but enough would to fill each nation’s ranks with another generation of leaders, officials, officers, and administrators.

Democracy presented a problem. If you abolish aristocracy, from where do leaders come? If there’s no class of people raised from birth with the expectation that they someday will have to lead, who will learn Greek and Latin and imbibe the wisdom of the great minds of classical antiquity? Who will lead men through hardship or into battle? Who will have the right notions of public-spirited honor to put the state’s interests above ambition and greed? This question became the heart America’s first political-party dispute.

Federalists like Hamilton hoped to build a new ruling class around what they called the natural aristocracy—what we today would call a meritocracy. Federalists hoped to find leaders among the dynamic strivers in cities, like lawyers and bankers, who would grow into a new class of leading families raised to administer and rule just like aristocrats in monarchies. Democratic-Republicans like Jefferson thought this sounded too anti-democratic and preferred to create a ruling class from “yeoman farmers”—wealthy local landowners and plantation magnates like Jefferson.

Neither the Federalists nor the Democratic-Republicans entirely won the battle over how America would create a new cadre of legislators, scientists, administrators, and officers. Ultimately, we did some of both, creating a new elite of bankers and lawyers in cities, while also elevating local landowners and business owners. This created a new democratic aristocracy.

THE OLD AMERICAN ARISTOCRACY

For the first part of America’s existence, this new democratic aristocracy served as its elite. As opposed to closed European aristocracies, ours was loose and porous so those with talent and accomplishment could win a place. John Jacob Astor, a German-born fur trader, got rich and created the aristocratic Astors. John Rockefeller, a clerk who built an oil empire, created the Rockefellers. Joseph Kenney, born to a Boston Irish-Catholic political family, built a fortune in business and securities (as well as some bootlegging) and created the Kennedys. These new families joined the social register with America’s founding families like the Adamses.

While the American aristocracy was porous, that doesn’t mean it wasn’t a real and powerful aristocracy. A group of great families raised their children from birth to ascend to the nation’s leaders. New families could join them, but there were obviously great benefits for those already in the club. Scions of these families trained at places like Harvard. In those days, Ivy League schools weren’t training grounds for academic strivers but for the aristocracy. Students learned Latin and Greek and read the great works of history, but also learned leadership, character, and the social manners of those in their position. In return, doors opened and opportunities fell into their grasp that ordinary Americans could never hope to win. These are the people we call the WASPs—although, like the Kennedys, not all were Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, or of Mayflower stock.

There were problems with this old aristocracy, not the least of which was it was anti-democratic. It’s impossible to justify why, in a democracy, unexceptional children from certain families should have special claims to leadership and privilege. The one great benefit of this aristocracy, however, was it groomed its members to lead and serve. It taught that privilege came with a solemn obligation to look out for those under your direction—noblesse oblige. This ethic spread throughout not just the aristocracy, but also to all the outsiders who mimicked its ways to rise themselves.

Milton Hershey, born humbly as a Pennsylvania German, got rich in the chocolate business, which ushered him to the heights of the aristocracy. Like many in his class, Hershey believed he had an obligation to look after his workers like a parent. He built Hershey, Pennsylvania as a model town to look after the needs of those working in his chocolate factory. The capstone of his project was Hershey Park, a great pleasure park opened so workers could enjoy a sense of community, fun, and relaxation.

Imagine an American company doing such a thing for its factory workers today.

THE RISE OF THE MERITOCRACY

After the Second World War, America changed how it trained its future leaders. This shift was gradual, and it happened for complicated reasons, some practical and some philosophical.

The shift began in the early twentieth century, as new groups began to rise in America, pressuring the old aristocracy to make room. The Ivy League began focusing on academic achievement as well as social background—leading to tensions as new groups began taking more spots, particularly Jewish students. After the war, this trickle of entrants became a flood. Defeating fascism caused Americans to see the nation in a more idealistic light, as a great free meritocratic democracy. As important, America’s new role in the world would require more skilled administrators and managers, which would require a greater number selected for competence, talent, and skill. This rocky process was in many ways like the one that saw Rome gradually extend citizenship outside the city into the far reaches of the empire, or wealthy merchant families during the Renaissance and Enlightenment gradually push into halls once reserved for landed nobles. If America was going to run an industrial democratic empire across the world, it needed a more meritocratic model.

The old aristocracy finally broke and began to fade away.

Until recently, I would have never dreamed of questioning the rise of America’s meritocracy. The old aristocracy was privileged and exclusionary. Young men and women of modest talent were trained to take roles they hadn’t earned, weren’t interested in, and often at which they had little hope of excelling. There was no reason this small lucky group should be handed the unearned privilege of leading a great power and democracy like America. The new meritocracy, moreover, was also good for people just like me—an Italian Catholic born in middle-class Chicago. It’s the reason why I could attend Princeton alongside other middle-class strivers, something the old aristocracy would never have permitted.

On the other hand, the meritocracy turned out to have a hidden downside—a lack of noblesse oblige. Aristocracies inculcate noblesse oblige because they know they have privilege they didn’t earn. Their claim to leadership is thus precarious. For people to tolerate hereditary rulers, those rulers must rule well and look out for those they rule. They must be better than ordinary people at running things, and must hold each another to higher tests of character than someone off the street. If they don’t, and they fail to rule wisely or well, the people will eventually rise up to take away their unearned privileges.

Meritocrats have no such need for justification. Their justification for ruling is they’re better and they earned it.

THE PROBLEM WITH MERITOCRATS

Meritocracies have two problems aristocracies don’t. First, because meritocrats are told they earned their position by merit, they don’t believe they owe anyone their service. Aristocracies demonstrate noblesse oblige to justify their unearned position. Meritocrats think they earned their position and therefore should enjoy the spoils. A meritocrat doesn’t think they took on a duty, but rather that they won a contest. Why would a winner owe a loser anything after beating them fairly at the game? The loser should have worked harder or been more talented. The meritocrat also doesn’t believe character is relevant to success, since it was academic tests, not tests of character, that selected them.

The second problem is someone must select and credential a meritocrat. Aristocracies choose members by royal decree, or the recognition of other aristocrats. Meritocrats, on the other hand, are credentialed by institutions. This leads to questions. By what right do these institutions get to pick their nation’s ruling class? Who picked these people to do the credentialing, and what standards are they applying? In a democracy, such matters should be under democratic control with transparent rules, but in reality they’re opaque and often arbitrary.

Once credentialing institutions exist, moreover, they become an attractive target for anyone who hopes to use them not to identify merit by a transparent recognized measure, but to engineer who and what is considered meritorious. Soon such institutions are no longer measuring recognized and neutral measures of merit, but wielding the power to decide who rules the democracy. They become kingmakers and unelected social engineers reshaping the democracy without a sense of duty or democratic consent.

We were naïve. We wanted to establish a meritocracy, but we gave too little thought to how one actually creates a ruling class. No one wants to go back to the old ways of the aristocracy. We need some way to recognize and train leaders—administrators, scientists, governors, and officers. The Meritocracy we implemented, however, has failed and arguably is corrupted.

I’ll be writing more about this problem in coming months. This problem of meritocracy is at the root of many of the problems now tearing us apart. It’s bigger than just bad “elites.” It’s about a larger unexamined philosophical question of how do you institute a transparent, fair, and competent method to decide who gets to be a leader in a democracy, and what their obligations as leaders should be. Few in public life, and neither major party, is talking about or thinking about this problem yet.

It’s should be a focus of any effort at national reform because whomever solves it will win the future of America.

What do you think about the rise of the meritocracy? Join the conversation in the comments.

Another problem is the validity of the credentialing. I know of a situation where a public official with a Ph.D. in leadership is quite obviously failing in some basic aspects of leadership.

A fascinating article, not only about the idea of "the meritocracy," but also about the importance of credentialing organizations. One thing I'd like to see discussed: How much of what is identified here as a commitment to public service (which would be totally laudable) is actually a lust for political power, dressed in less objectionable clothes?